My earliest technological memory is the alphabet. Specifically, as learned from observing a poster in my childhood room. The poster depicted the alphabet enacted by a pair of models photographed in the shape of each letter. The ‘A’ had them leaning head to head, extending the lower arm to form a bridge. The ‘P’ had one crouching on the back of the other, who was standing erect. A curious design artifact of the early 80’s, exposed to me as a toddler, provoking much curiosity.

I don’t remember when it changed, but at some point in my early childhood the letters acquired sounds and could be strung into sequences with meaning. I became an avid reader, devouring encyclopedias and novels before my first year in school.

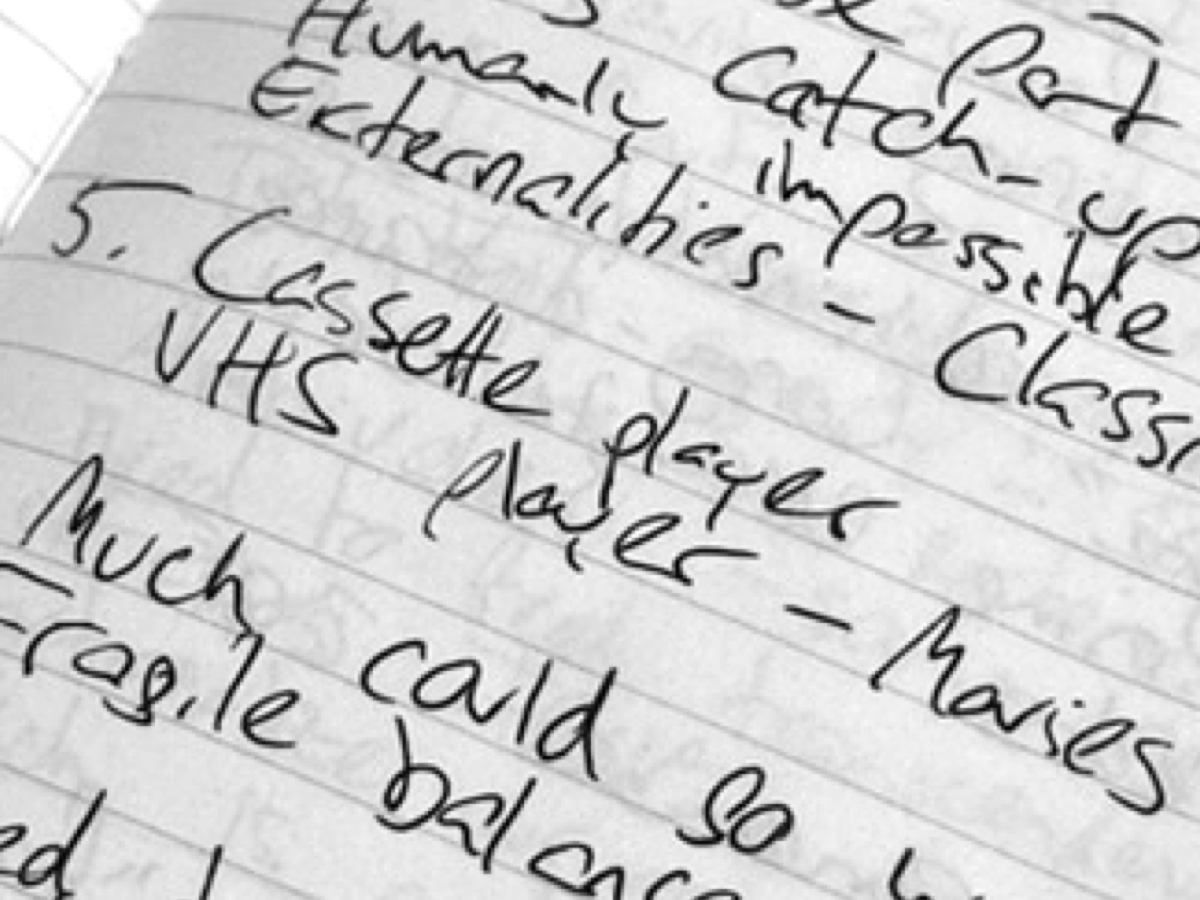

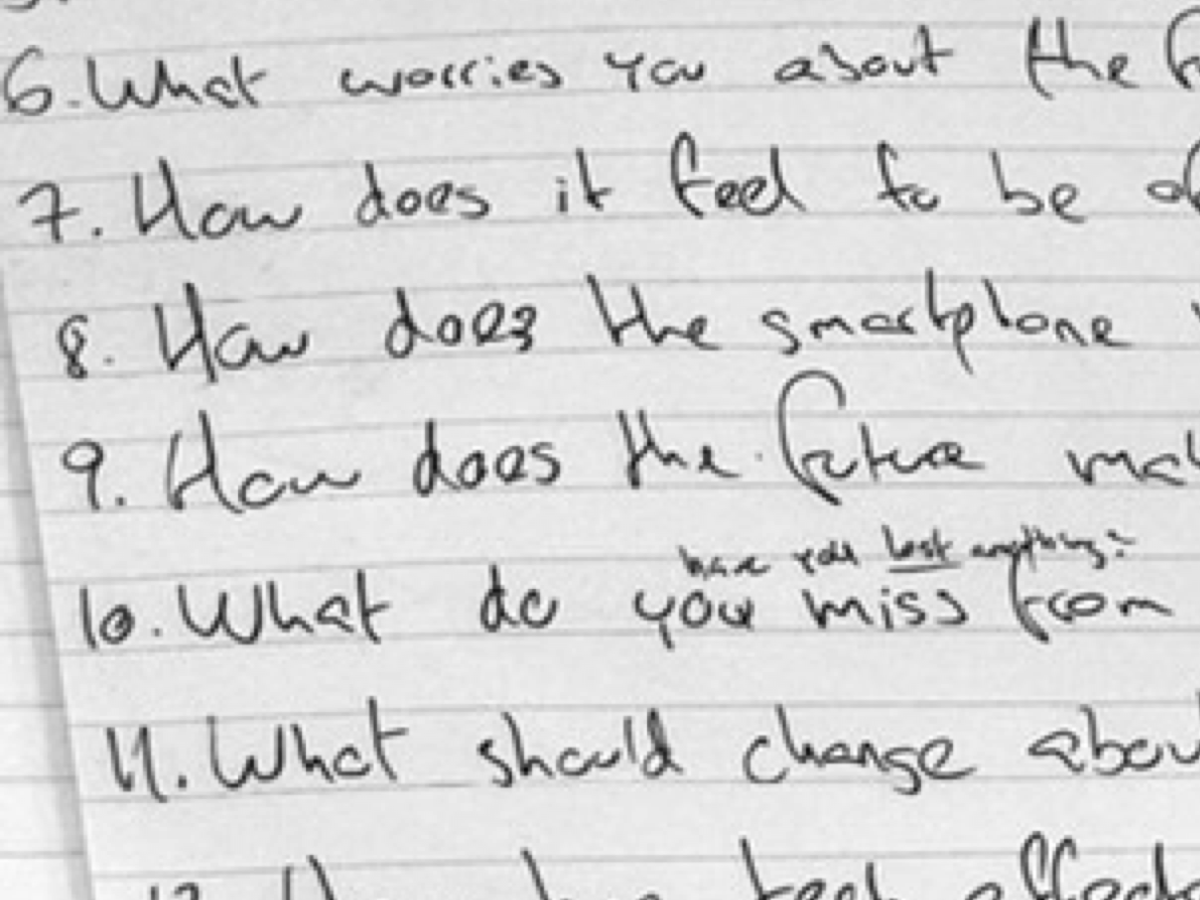

When I ask people this question, an array of answers emerge, but most gravitate towards forms of media as their earliest technological memory.

Television, radio, cameras, telephones, video games and personal computers. Sony’s Walkman is often spontaneously mentioned for people born in the eighties, along with Nintendo and Sega consoles. A remarkable amount of interviewees voluntarily cite Tamagotchi, the virtual pet requiring constant attention for staying alive. Perhaps a precedent for how we engage with smartphones decades later.

While half the answers are media-related, a significant amount of respondents ask to reframe the question, establishing a broader definition of technology. Going beyond electronic devices, one can consider everything not of the natural world as technological. Acknowledging this, they cite toys, bicycles, cribs, kitchen appliances, typewriters, clothes and even speech as their first recollection of using a technology.

The ages people relate having these memories range mostly from 3-8, correlating with our earliest memories in general.

What stands out is how almost all answers revolve around objects. Artifacts we engage with physically. All external, all things that are interacted with.

Language might not be characterized as being technological, but so far nobody has mentioned play, socialization or painting – all of which children frequently do, and could be considered technological. Perhaps because of their inherent nature – because how deeply ingrained these activities are – meaning we don’t associate them with technology. We don’t see them as such.

Writing these words next to a playground littered with young children, this is particularly poignant. I see kids digging in the sand, telling stories, chasing each other and jumping from swings – none of which have been cited as technological memories.

The alphabet is artificial, a construction of symbolic manipulation. However, play – and creation – are in our nature. They are inherent, not fabricated. Extension of how the natural world works.

Berlin 12 June 2019